As we inch warily or rush enthusiastically into another year against a backdrop of political turmoil and business uncertainty in major markets, it is time to look at the prevailing 2019 pharmaceutical industry trends and what they might mean for companies launching new medicines, negotiating market access barriers, or simply trying to do what they do better. Inevitably, the US is in the thick of the action. But there are many other important 2019 pharma trends, both national and global, that will set the pace for industry throughout what promises to be another dynamic and challenging year.

As we inch warily or rush enthusiastically into another year against a backdrop of political turmoil and business uncertainty in major markets, it is time to look at the prevailing 2019 pharmaceutical industry trends and what they might mean for companies launching new medicines, negotiating market access barriers, or simply trying to do what they do better. Inevitably, the US is in the thick of the action. But there are many other important 2019 pharma trends, both national and global, that will set the pace for industry throughout what promises to be another dynamic and challenging year.

To the world outside the United States, Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ rhetoric may sound tiresome, truculent or outmoded. To the pharmaceutical industry, though, the US remains, unavoidably and by some margin, the world’s single largest market for medicines. It is the place where big money can be made to offset more stringent controls on pricing and market access in other territories.

Commentators and politicians leaning to the right like to paint this trade-off as the US subsidising lower prices and drug costs in Europe and other ‘freeloading’ regions committed to ‘socialised medicine’. Not surprisingly, President Trump has taken these arguments to heart in his fitful but determined assaults on drug price inflation in his home market.

Trump recently delivered a proposal for taming pharmaceutical costs in Medicare that looks remarkably like the external reference pricing routinely employed by many more financially constrained (or disciplined) healthcare systems around the world.

With the Democrats taking the House of Representatives in mid-term elections, all bets are off as to whether this will make price-control measures easier or more difficult to push through the US legislative process. But the reference-pricing proposal and related initiatives do illustrate the degree of interaction and connectivity in an ever more globalised pharmaceutical market.

Companies that have always relied on the US to take up the slack from market-access restrictions elsewhere may be watching nervously for Trump’s next move, and perhaps welcome the potential stalemate implicit in a split Democrat House and Republican Senate. Yet recent efforts to galvanise a moribund biosimilars market in the US are another indication that the administration is taking a tougher line on drug costs.

So in our predictions for 2019 we’ll be highlighting the continuing interplay of global and local pharmaceutical industry trends. And that, of course, also shapes pharmaceutical new product launch strategies and market access in a global, yet still often very locally specific, environment.

We’ll look at how some of the influence is going in unexpected directions, such as the potential (however tentative) for external reference pricing in the US; and how another important market, the UK with its still dangling Brexit negotiations, is on the cusp of what could be a highly disruptive break with harmonisation in conditions for the regulation, sale and distribution of medicines.

At the same time, there are overarching global trends, such as the more assertive presence of biosimilars, the expected slowdown in drug-market growth, or a narrower focus on value creation in R&D, that could have far-reaching implications for the way in which the pharmaceutical industry conducts its business, wherever it conducts that business.

Pharmaceutical Industry Trends for 2019

Trend #1: Sales growth is slowing

Given the ever more daunting market access challenges to pharmaceuticals in established or developed territories, such as the US and Europe, it is hardly surprising these markets are reaching some degree of saturation.

That puts the onus on companies to provide real innovation, well-defined product differentiation, measurable cost-benefit advantages or meaningful quality-of-life improvements for patients.

At the same time, pharma has taken some comfort from a growth surge in fast-industrialising emerging markets, particularly those with large populations and substantial unmet healthcare needs, such as China, India or Brazil.

With economic advancement, these countries are looking at ways to expand patient access to high-quality healthcare. At the same time, pockets of new wealth are stimulating demand for cutting-edge treatments in the private sector. All of this creates opportunities for medicines of every stripe.

Emerging markets are by no means a sure thing, though, quite apart from the need to address evolving systems of regulation or pricing and reimbursement that may be obtuse, tailored to local policy goals, or out of sync with market development.

According to recent forecasts by the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science, net sales growth for branded medicines is flattening out in developed markets. But it is also starting to falter in those emerging markets that have provided relief from tougher conditions in the developed world.

Expanding healthcare access in emerging markets inevitably means taking a hard look at cost drivers and cost efficiencies. Sheer expediency always makes pharmaceuticals an easier target for economies than sunk costs like infrastructure or politically sensitive measures such as reducing staff counts.

Moreover, in many developing countries, most of the spending on innovative medicines still comes from patients themselves. This results in a highly polarised and segmented drug-funding environment, of questionable sustainability in the longer term.

In its recent report 2018 and Beyond: Outlook and Turning Points, IQVIA says net spending on branded medicines in developed markets – which includes the considerable impact of statutory or negotiated pricing and reimbursement concessions – rose by 21% from $326 billion to $395 billion over the last five years, with the US supplying 87% of the $69 billion in net growth during that period.

In 2018, IQVIA believes, net brand spending in developed markets will decline by 1-3%. And over the next five years it expects brand expenditure on pharmaceuticals in these markets to stay flat, despite a continuing stream of new product launches.

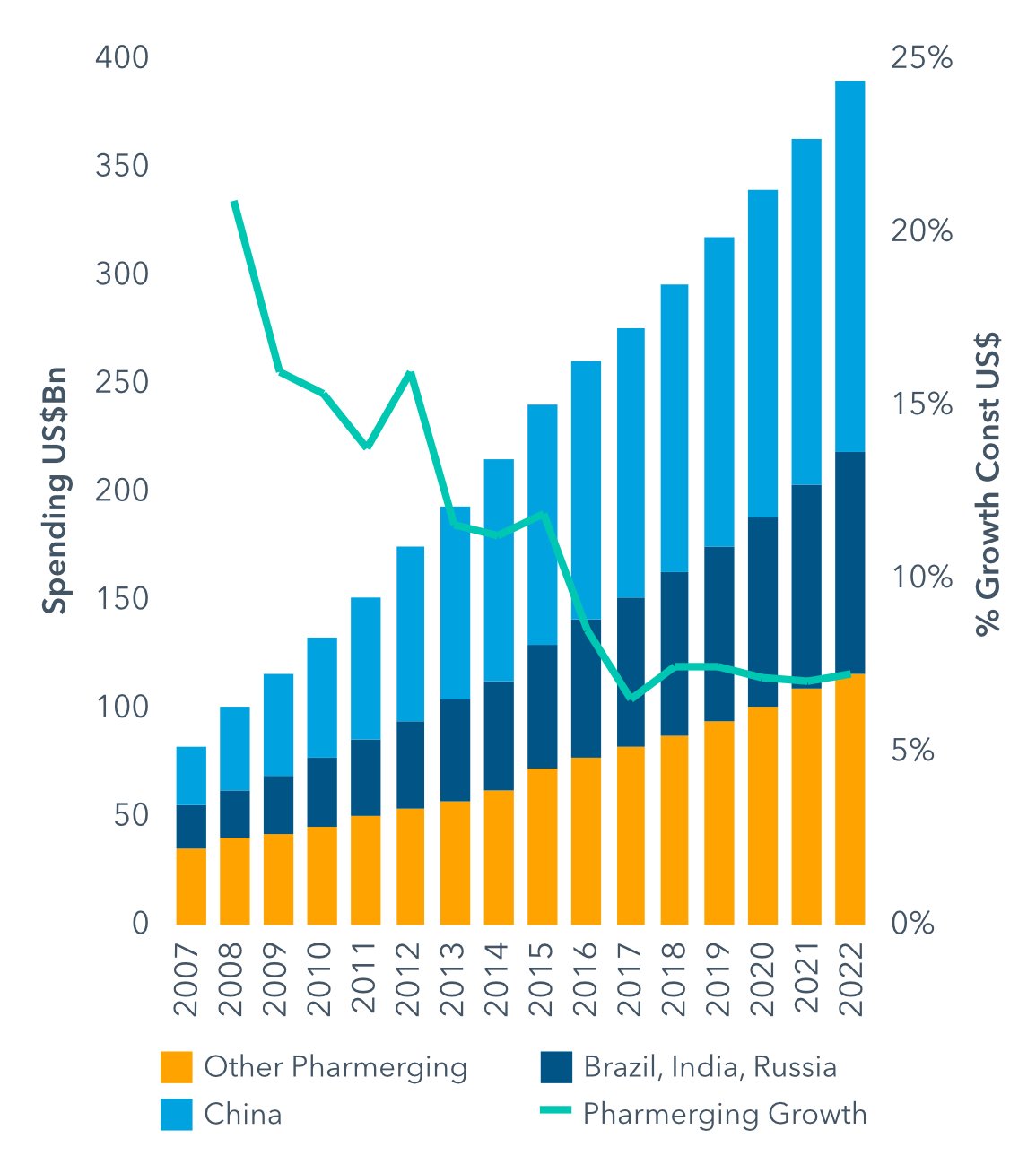

Turning to its basket of ‘pharmerging’ markets – defined as having per capita income below $30,000 and five-year aggregate pharmaceutical growth of more than $1 billion – IQVIA notes that these countries’ share of global expenditure on medicines expanded from 13% in 2007 to 24% in 2017, or in value terms from $81 billion to $270 billion.

The average growth rate for drug spending in pharmerging markets was 12.8% over this period, more than twice the rate of global growth, IVQIA reports. However, growth across these countries is projected at 7-8% for 2018, whereas over the previous five years the compound annual growth rate was 9.7%.

In the years to 2022, drug-spending growth in the pharmerging markets is expected to slow down to 6–9%, lifting expenditure from $345 billion to $375 billion. The largest of these markets, China, will expand by only 5-8%, to $145-175 billion, over the next five years, IOVIA predicts.

It also foresees a deceleration of spending growth in other major pharmerging markets such as Brazil, India and Russia, where less dynamic economic growth overall is taking its toll on pharmaceutical sectors with high out-of-pocket costs.

Pharmerging Markets: Medicines Spending and Growth 2007-2022

Source: IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science

Source: IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science

For most pharmerging markets, IQVIA points out, achieving full access to healthcare for is “a complex balance of encouraging investment while also discouraging growth that makes medicine unaffordable to individuals”.

The message for pharmaceutical companies prepared to go the distance in developing markets, on the promise of fostering long-term growth, is these countries are no holiday from market access barriers; they just apply those barriers differently.

Moreover, the fundamental drivers of market access restrictions, be they population aging, chronic disease, sedentary lifestyles or rising awareness of, and demand for, state-of-the-art therapies (see our blog on Maintaining pharma ROI as market access bites), are essentially similar the world over.

As emerging markets continue to grow, albeit at a more subdued pace, we are likely to see increasing convergence in the market-access environment, coupled with the very particular challenges of persistent local variations. For the pharmaceutical industry, the world may be getting smaller every day, but complacency is not an option.

Trend #2: Biosimilars get serious

The last few years have seen biosimilar versions of biological medicines emerge as a serious opportunity for healthcare systems to ease the financial burden of premium-priced originator biologics, while widening patient access to biological products overall.

With the needle now shifting from relatively straightforward biologics such as erythropoietins or human growth hormones to more complex monoclonal antibodies that address chronic, age-related and costly conditions, like cancer or rheumatoid arthritis, the biosimilars market is at last beginning to accumulate some critical mass.

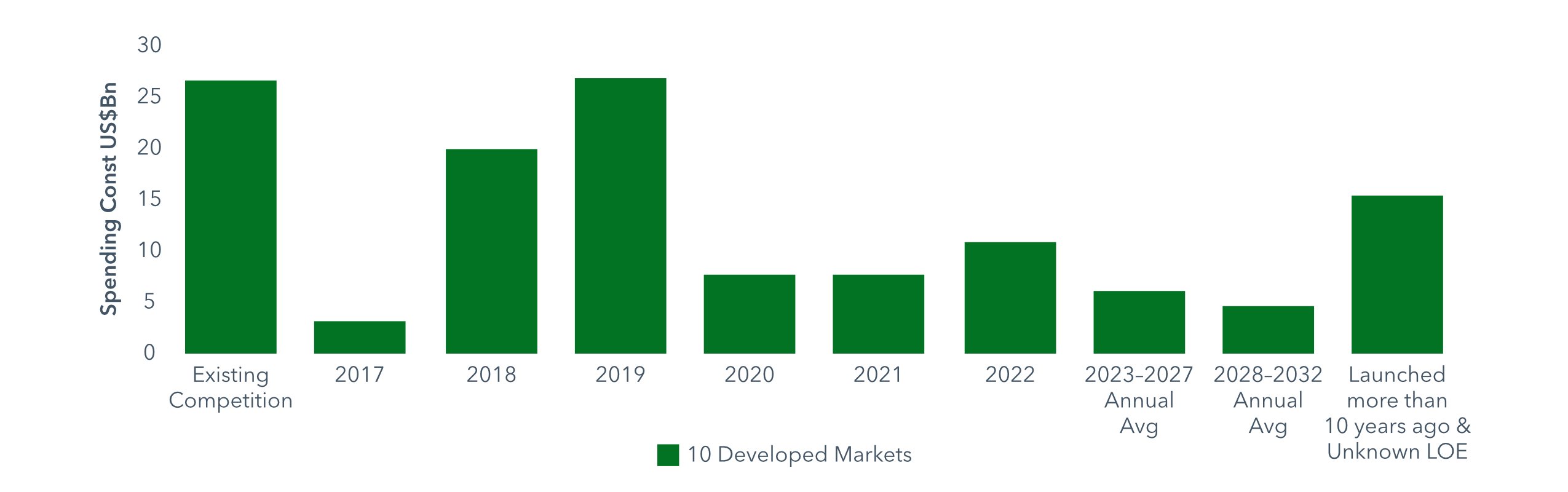

According to the IVQIA Institute for Human Data Science, $19 billion of spending on biologics was laid open to biosimilar competition for the first time in one or more of the developed markets during 2018. This was substantially more than the $3 billion exposed to competition in 2017, and came on top of the $26 billion in biologics spending already up for grabs in 2018.

The IQVIA report forecast that another $52 billon in biologics expenditure would face biosimilar competition in developed countries between 2019 and 2022, $37 billion of which would be in the US. By 2027, 77% of current expenditure on biologics would be subject to some form of competition, IQVIA said.

Biologics Spending Newly Exposed to Biosimilars 2017-32 (2016 values, US$ bn)

Source: IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science

A particular turning point in what IQVIA called “the next large wave of biosimilars” was the exposure of AbbVie’s blockbuster biologic Humira (adalimumab) to biosimilar competition in Europe from October 2018. Humira is the world’s leading medicine by sales value, bringing in revenues of $18.4 billion in 2017 and accounting for something like 60% of AbbVie’s whole turnover.

Nonetheless, uptake of biosimilars, and the incentives provided for uptake, still vary considerably from market to market. They range from purely price-driven tenders in Scandinavian or Central and Eastern European countries, to value-driven commissioning of biologics in England’s National Health Service, or pharmacist authority to substitute biosimilars under defined circumstances in France.

At the same time, some doctors remain sceptical about the long-term implications of switching patients to biosimilars and some countries are distinctly behind the curve on uptake. Notable among these is the US, where – as the IQVIA forecasts suggest – biosimilars are still only really getting started.

This is partly because the US was slow compared with other key markets, such as the European Union, in laying out and implementing a distinct approval pathway for biosimilars; and partly due to competitive factors - for example, the particular strength of patent defences in the US, where Humira remains protected from biosimilar incursions until 2023.

To date, the European Medicines Agency has approved close to 50 biosimilar products and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) only 13. Moreover, originator companies have found other ways to block biosimilar uptake in the US, such as preferential contracting arrangements with payers.

The US courts and administration have recently taken some steps to remedy this situation and jump-start market competition for biosimilars, such as the Biosimilars Action Plan published by the FDA in July 2018.

Announcing that initiative, FDA Commissioner Gottlieb noted that biologics accounted for 70% of the growth in US drug spending between 2010 and 2015. So far, Gottlieb pointed out, only a handful of biosimilars had actually been launched in the US, and competition had been, “for the most part, anaemic”.

Clearly the rising tide of biosimilars presents market-access challenges to research-based biopharmaceutical companies that have been making hay with premium-priced biologic assets. Some companies have risen to that challenge by joining the party, so that hybrid biologic-biosimilar concerns, such as Novartis or Amgen, are an increasingly common feature of the biosimilars market.

his trend will help to establish biosimilars as an integral component of a pharmaceutical market balanced between innovation, affordability and access, just as chemical generics have helped to free up space in drug budgets for more expensive mainstream pharmaceutical brands.

Some question marks remain over the future of biosimilars, such as whether demand or drivers for uptake are really strong enough, given the relatively modest discounts available on originator biologic prices; or, alternatively, whether more vigorous biosimilar competition around blockbusters such as Humira will lead to price erosion and a commodity market that threatens long-term sustainability.

One thing is for certain, though: biosimilars are taking off, they are for keeps, and market access for biologics will never be the same again.

Trend #3: Pricing still on the menu

Another emerging trend where all eyes are on the US is the Trump administration’s moves to tighten up conditions for drug pricing and related instruments such as rebates and discounts.

This is a familiar story, of course, in Europe and other countries inclined to centralised controls on healthcare costs, and where health technology assessments of drug value now regularly intervene as a ‘third hurdle’ between marketing approval and pricing or reimbursement negotiations.

But the US has usually favoured market-oriented approaches to cost-containment, such as horse-trading between pharmaceutical companies and pharmacy benefit managers, the measures to stimulate biosimilar competition outlined above, or Commissioner Gottlieb’s recent efforts to facilitate approvals and usage of generic drugs through more efficient review processes and up-to-date labelling.

While the current administration is unlikely to suggest that free-market policies no longer work, it is undoubtedly showing its teeth on runaway drug prices, which were part of President Trump’s election platform and have provided him with reliable Twitter fodder ever since.

Moreover, drug-cost inflation, and specifically the prices of cutting-edge biopharmaceuticals, continue to exercise politicians, payers and patients alike. Unveiling the Biosimilars Action Plan, Commissioner Gottlieb noted that fewer than 2% of Americans used biologics, yet these products absorbed 40% of all prescription drug expenditure. Biologics were responsible for 70% of the growth in US drug spending between 2010 and 2015.

If US cost restraints are market-led, it is a malfunctioning market. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar recently made this observation on the way drug prices and doctor’s commissions are determined in Part B of the Medicare programme for the elderly: “It says, ‘Hey, manufacturer, invent whatever list price you want, and we’ll pay a 6 percent premium on top of that.’”.

Drug pricing in Medicare’s retail prescription-drug programme, Part D, is subject to competitive negotiations between private payers and pharmaceutical companies, based on levers such as formulary placement, discounting, rebates or step therapy (starting patients on the cheapest available and effective prescription drug).

The administration’s proposals for reference pricing in Medicare Part B, whereby reimbursement prices for drugs administered in doctors’ offices and hospital outpatient departments would be pegged to an international pricing index, is just the latest – and, at least in US terms, most radical – of a series of initiatives under Trump that attack pharmaceutical cost inflation on several fronts.

These include:

- Allowing Medicare Advantage Part C plans to apply step therapy to covered medicines.

- Leveraging the negotiating powers of Medicare Part D plans to certain medicines covered under Part B.

- Requiring Medicare Part D plans to apply a portion of negotiated discounts and rebates at the point of sale, so that savings are distributed more evenly.

- Reducing perverse incentives around the 6 percent doctor commission for Medicare Part B drugs.

- Closing loopholes that enable brand-name manufacturers to shut out generic competition.

- Pricing by indication for high-cost drugs in Medicare Part D.

- Restricting the use of rebates and drug co-payment discount cards.

- Demanding that pharmaceutical companies disclose the list prices of more expensive prescription drugs covered by Medicare or Medicaid in direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising.

Some analysts have suggested that the reconfiguration of the House of Representatives will leave President Trump’s pricing proposals in limbo. Nonetheless, the issue is unlikely to go away in 2019, however much pharma would like to see a return to normal in US drug pricing.

Democrats in the House are likely to push for broader healthcare coverage overall, which could mean closer scrutiny of pharmaceutical prices. Party leader Nancy Pelosi has already promised “real, very strong legislative action to negotiate down the price of prescription drugs that is burdening seniors and families across America”.

Trend #4: Brexit drags on

In last year’s look ahead at Pharmaceutical Industry Trends 2018, we sketched the political and economic turmoil around the UK’s pending exit from the European Union, as well as the possible consequences for pharmaceuticals both in the UK and Europe as a whole.

Sadly, one year on a cloud of uncertainty still hangs over the likely outcomes and impact of the Brexit negotiations. And if many of the general public have now reached exhaustion point with the endless horse-trading, carping and careerism that mark this less than glorious chapter in UK history, for the pharmaceutical industry it remains very much a live and worrying issue.

As a business and investment hub for medicines, the UK has already lost the considerable leverage of hosting the European Medicines Agency, now setting up its new home in Amsterdam.

Moreover, the pharmaceutical industry has made clear that Brexit could disrupt medicines supply and regulation across a broad range of parameters, including manufacturing, quality controls, safety, clinical trials, the drug-supply chain, intellectual property, parallel imports, employment, and the wider implications for an already hard-pressed National Health Service.

Now, with the plausible prospect of a ‘hard’ or ‘no-deal’ Brexit offering no special concessions for medicines, those warnings look all the more troubling. The continuing uncertainty over where the UK will be come the 29 March 2019 deadline for Brexit is playing havoc with business planning.

Reports of companies stockpiling or even preparing to use emergency airlifts for vital medicines are legion. The government has already asked companies and the NHS to stockpile six weeks’ worth of medicines, at a potential cost of billions of pounds, in case of a no-deal scenario – although this may not be enough for some medicines with limited shelf lives manufactured in the EU.

A coalition of UK industry associations for pharmaceutical, biotechnology and generic medicines, together with the NHS’ Brexit Health Alliance, recently warned in a letter to Matt Hancock, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care: “We do not believe that the current medicine supply plans will suffice, and we will have widespread shortages if we do not respond urgently.”

All of these arrangements come at a significant price, including the possibility that companies readying for a ‘hard’ Brexit will squander money and resources if negotiations end in a ‘no deal’, without the agreed transition period until 31 December 2020 under EU rules. Alternatively, companies may be investing heavily to manage the consequences of a ‘no deal’, with the risk of those efforts being voided by a last-minute Brexit agreement.

Particular unresolved areas of concern for the pharmaceutical industry in the UK are access to research and development funding; ability to continue collaborating across the EU in clinical research; trade capability and the free movement of goods across borders; maintaining a common regulatory framework within Europe; free movement of talent; and maintaining protection for intellectual property.

But these are really only the tip of the iceberg. And any interruption to the supply of medicines, however minor, could have grave consequences.

As Mike Thompson, chief executive of the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry, pointed out to the House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee in October, “the biggest issue is around patients not getting their medicines. This is not a situation where if we managed to get 80% of the medicines there, that is a good effort and it is okay. Every single patient is reliant on their medicine, so we have to do that for every patient”.

The digital revolution and physical migration have changed the way we all think about geography, national boundaries and nationality. It is a more mixed up world, in every sense.

Some of that goes in the direction of harmonisation and universality, which in a number of respects has provided the pharmaceutical industry with a more seamlessly integrated global marketplace. As the continuing Brexit negotiations illustrate all too clearly, though, with harmonisation comes resistance, and with globalisation comes a renewed and divisive focus on nationhood.

As we highlighted in our guide and checklist for risk management and new product launches, for pharmaceutical companies launching new products or negotiating market access, the mantra ‘think global, act local’ remains as pertinent as ever.

Trend #5: You too, pharma

Emma Walmsley - Chief Executive Officer of GlaxoSmithKline

Emma Walmsley - Chief Executive Officer of GlaxoSmithKline

Before the Me Too movement and all the associated debates around equalising opportunities for women while curbing toxic male behaviour reach boiling point, let us not forget that the pharmaceutical industry also needs to take stock on gender disparities.

At least at executive level, the industry remains predominately male (not to mention white, etc) – somewhat surprising, given that traditionally health is regarded as women’s terrain. There are a few notable exceptions, such as Emma Walmsley, chief executive officer (CEO) at GlaxoSmithKline, Sandra Peterson, group worldwide chair at Johnson & Johnson or Martine Rothblatt, CEO of United Therapeutics.

There are also some welcome signs of improvement. According to a study last year by The Massachusetts Biotechnology Council (MassBio) and executive recruiting company Liftstream, women are entering the lifesciences industry in equal proportion to men (49.6% versus 50.4%).

However, when it came to the C-suite level, women in the MassBio-Lifestream study were filling only 24% of positions versus 76% for men, while female representation on the boards of life-sciences companies was even lower at 14.4%

This waste of talent has not gone unnoticed by industry. For example, in the US the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) has established principles on workforce development, diversity, and inclusion (WDDI), which include raising the proportion of women in company leadership positions to 50% and at board level to 30%.

Ultimately, there is no earthly reason why women should not be as rich in the same qualities of leadership, innovation, insight, organisation or strategic acumen that have put countless men in pharma C-suite positions over the years.

Will women do it any better? For example, it could be argued that the current crop of female pharma executives will achieve more, simply because they had to try harder to attain those positions in the first place.

In the end, it is the wrong question. Incompetence, hubris, bullying, bad decision-making or questionable ethics are often gender-neutral, in business as much as anywhere else. It is clear women must have every opportunity to make the same mistakes men have always made – or alternatively not.

More pharma women into positions of power – and fewer ‘pharma girls’ on the rep circuit – will not only clear the air but create opportunities to do some things differently.

Women, for example, may have more reason than men to favour flexible working.

And even the most politically correct of us can allow that some women may communicate differently, plan differently, see things differently, or collaborate differently in the workplace.

With the current multiple restraints on industry from healthcare cost-cutting, the proliferation of digital technologies that have revolutionised communications with key stakeholders (as well as creating a new breed of connected, informed patient), and the emerging gene and cell therapies that may change the whole emphasis of what pharma does, fresh thinking from any direction is more than welcome.

Will better representation of women in key roles usher in a new mode of pharma? That remains to be seen. This is conservative industry, closely watched and regulated. It moves slowly, whatever the pace set by technological change in overlapping sectors such as digital technology or advertising.

Hopefully, 2019 will see a determined push for a gender-equal and -equitable environment in which gender itself will eventually become irrelevant.

The pharmaceutical industry needs the best talent it can get. Putting up artificial barriers to women who can address that need makes no business sense at all, let alone being woefully out of synch with gender politics in enlightened societies.

Trend #6: Value-focused R&D

In today’s increasingly value-focused environment for pricing and reimbursement of medicines (see our blog on 'Getting Your Launch Strategy Right for Today’s Market Access Paradigm'), pharmaceutical companies simply cannot afford also-rans.

That means research and development pipelines need to generate meaningful innovation: not just marginal improvements in drug efficacy or safety but therapies that really transform healthcare.

These may take a whole new approach to intractable diseases, such as gene therapies or immunotherapies for cancer. They may redesign treatment pathways to provide more effective, cost-efficient care that protects drug budgets.

Alternatively, meaningful innovation may provide both significant therapeutic benefits and measurable cost offsets, such as reducing expensive hospital stays. Or it may improve the patient experience, through better tolerance, more convenient drugadministration, enhanced quality of life or reduction of stigmatising symptoms.

All of this underlines how much, as we move into 2019, pharmaceutical companies must think hard about what their core offering is, and where they fit into an ever more intricate and expansive healthcare equation. That is to say nothing of addressing the alarming rise in ageing- or lifestyle-related diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, cancer, arthritis or diabetes.

Inevitably, then, we will see tough decisions being made and R&D pipelines pared down more and more to concentrate on essentials, ensuring that research efforts are truly value-oriented.

Value, of course, is multifaceted: what looks like a scientific breakthrough for a pharmaceutical company may not look so attractive to a cash-strapped budget manager or health technology assessor, and it may not address the full scope of patient needs in that category.

One notable pointer towards more tightly focused R&D was the news in October that Novartis had dropped 20% of 430 drug-development programmes, including therapies for infectious diseases, following a pipeline review. The Swiss company made clear it was prepared to sacrifice perfectly valid scientific concepts for something potentially more “transformative”.

Novartis is by no means the only pharmaceutical multinational re-examining its R&D priorities. When Emma Walmsley took over as CEO at GlaxoSmithKline, for example, she was quick to overhaul the company’s research and development operations, closing down more than two dozen clinical trials as the pipeline was recalibrated to specialist areas such respiratory disease, HIV and oncology.

More recently, there have even been indications that GSK may abandon its long-established respiratory heritage in the face of generic competition and increased pricing pressure.

Pfizer, on the other hand, has hedged its bets by scrapping early-development programmes in neuroscience but subsequently partnering with Bain Capital to create a new company, Cerevel Therapeutics, dedicated to drug development for disorders of the central nervous system.

In a marketplace where delivering value on multiple fronts is the key driver of product differentiation and uptake, pharmaceutical companies will continue to re-assess their R&D pipelines dispassionately, if not ruthlessly, in an effort to stay competitive, negotiate market-access barriers and keep shareholders happy.

Hopefully, this sharper focus and declared commitment to meaningful innovation will pay dividends for patients in need as well.

Andre Moa

Andre Moa

14 Jan 2019

14 Jan 2019

24 minute read

24 minute read