The pharmaceutical market is always challenging, and 2017 has been no exception. As we look ahead to some key pharma trends for 2018, we find certain hardy perennials, such as drug pricing, that re-emerge in new iterations year after year.

Others trends, such as new gene therapies or the disruptive opportunities afforded by digital-health technologies, are evidence that science continues to push the envelope and ask crucial questions about how pharmaceuticals might be discovered, developed, delivered and funded in the future.

Then there are issues marooned in uncertainty, such as the outcome of the UK’s Brexit negotiations with the European Union. These dilemmas will seep into 2018, with no firm indications as to what they will mean for pharma planning and business strategies.

Here, then, are six key trends that we believe will set the course for the industry in 2018, whether that is into choppy waters or new depths of possibility. Some of these pick up on themes featured in our pharmaceutical industry trends 2017 blog post.

Others illustrate how the whole ecosystem in which industry operates, and the number and variety of stakeholders across the medicines enterprise, continue to expand in ways that confront traditional modes of drug discovery, development, supply, marketing and payment.

They bring new shades to the ongoing debate about what the pharmaceutical industry, in an age where ageing and health are more central than ever to the economic, social, political and ethical evolution of our societies, is really for.

NEWS: Our latest trends blog Top 6 Pharma Trends for 2019 is now published. Why not check it out?

Key Pharma Trends for 2018

Trend #1: Where's the value in it?

As cost pressures on healthcare systems continue to escalate worldwide, more and more pharmaceutical companies are talking about the need to embrace value-based pricing, contracting and reimbursement.

There are pioneers in this field, both at the level of national healthcare systems (e.g., Italy, Spain, Australia) or insurers and pharmacy benefit managers in the US (Harvard Pilgrim, Advocate Health, Express Scripts), and within the pharmaceutical industry itself(Roche, Eli Lilly, Amgen, Sanofi, Novartis, Merck & Co.).

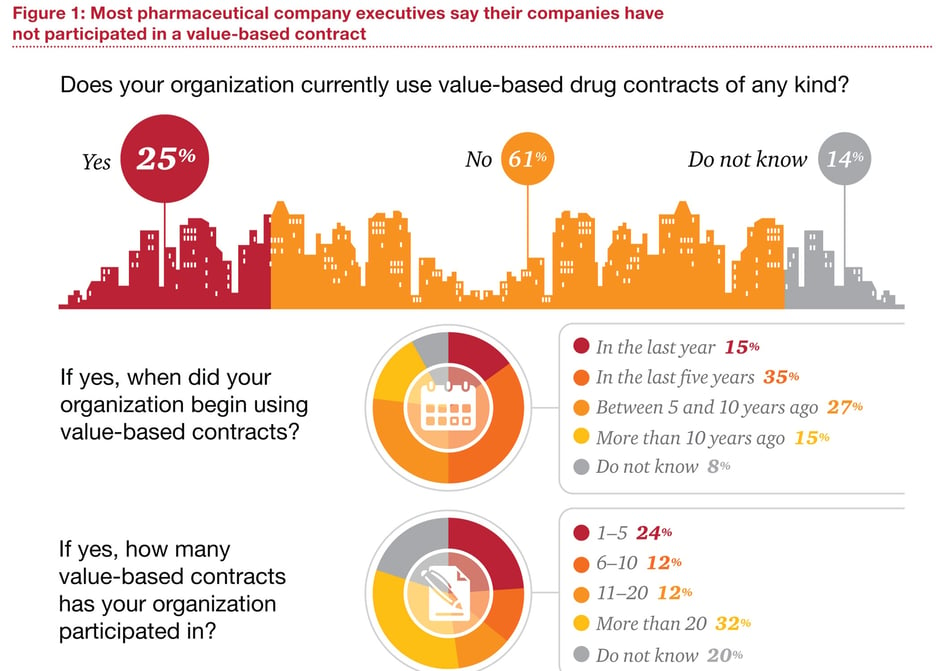

For all the talk, though, value-based contracting is still not much more than a provisional strategy for balancing innovation and access in the pharmaceutical market. In a recent survey of 101 pharmaceutical executives and 100 health-insurance executives by PwC's Health Research Institute, only 25% of respondents said their organisation was engaged in value-based contracting of any kind.

Source: PWC

Among pharma executives who had participated in value-based contracts, 80% described the experience as ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ successful. Moreover, 71% agreed that value-based contracts could improve patient outcomes and reward manufacturers for bringing innovative and effective products to market. Yet only 38% felt the potential rewards of value-based contracting were commensurate with the risks.

Conversations about pricing, value and outcomes will continue during 2018. That includes the growing trend to volume-based bulk purchasing highlighted in our new Tender Management Checklist.

With ageing populations and chronic disease weighing on health systems across the developed and developing world, stop-gap, reactive solutions to drug-cost inflation are no longer an option. That is unless industry wants to resign itself to budget caps, formulary exclusions, stringent pre-authorisation conditions and other market access barriers.

In the US, there are indications that the Trump administration’s tough line on premium drug pricing has eased somewhat, at least in terms of targeting industry. But state-level initiatives, such as the recent drug price-transparency law introduced in California, are stepping into the breach.

Value-based contracts means addressing a range of issues that dilute commitment from pharmaceutical companies and healthcare payers, such as defining and tracking value, designing and administering outcomes-based payment systems, or integrating patient data across siloed healthcare infrastructures.

Among emerging trends in the pharmaceutical market, data – and its potential to supply real-world evidence that underpins value-based contracting – will need to sit at the heart of these efforts. As we noted in our Launch Readiness Checklist 2.0, managing and coordinating launch activities worldwide relies on effective sharing, analysis and reporting of real-time data, with a free flow across functional and geographical silos.

Data management is another area in which industry has been building up resources but could do more. A recent analysis by LinkedIn found there were 2,302 data scientists employed by healthcare companies as of November 2017, compared with 876 in November 2015.

Yet the perception is still that the heavily regulated and slow-moving pharmaceutical industry needs to make better use of the data it has. As Mark Ramsey, senior vice president and chief data officer at GSK, put it: “What I quickly found is the pharma industry is a lagging industry … It produces a lot of data, but [it doesn't have] a history of maximizing the value of that data.”

Trend #2: Brexit is a European medicines issue

For all the nagging uncertainty arround the UK's status once it breaks definitively with the European Union in March 2019, the rest of Europe can hardly be blamed for feeling their one-time ally is in a pit of its own making.

The UK should expect few concessions in extricating itself from an arrangement which many of its citizens and political cheerleaders have vocally denounced as inefficient, corrupt, self-serving or destabilising.

For the pharmaceutical industry, the most immediate consequence of this bulldog spirit – or reckless hubris, depending on your perspective – was the loss of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to Amsterdam following the relocation vote by EU ministers on 20 November. Located since 1995 in London’s Canary Wharf, the EMA has made the UK a magnet for regulatory expertise and inward investment by the pharmaceutical industry and its satellites.

It has also given the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), and sister agencies such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), considerable influence over drug regulation and uptake in Europe and beyond.

This applied particularly in areas such as clinical trials, pharmacovigilance and accelerated-approval mechanisms. Between 2008 and 2016, for example, the MHRA acted as Scientific Advice Coordinator in at least 20% of drug-approval procedures handled by the EMA centrally, and provided data in around 50% of EU approval procedures.

The UK will be doing its best to retain some of this influence and investment through industrial strategy, such as its recent sector deal on investment with the life sciences industry, and other means in the post-Brexit environment.

From the EMA’s perspective, though, and that of ongoing medicines regulation across the EU, Amsterdam was among the best possible outcomes in terms of staff retention, available facilities and continuity of service.

Yet the pharmaceutical industry insists Brexit is far more disruptive to medicines supply than its impact on the UK alone might suggest. It takes in issues such as manufacturing, quality controls, safety, the drug-supply chain, intellectual property, parallel imports and employment.

For example, a survey conducted among member companies by the European Federation for Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) found that:

- More than 2,600 final medicinal products include some stage of manufacture in the UK.

- 45 million patient packs are supplied from the UK to other EU27/EEA (European Economic Area) countries every month.

- Over 37 million patient packs are supplied from the EU27/EEA to the UK each month.

Moreover, around 17% of centrally authorised marketing authorisations for medicines in Europe are held in the UK and will need to be relocated to a EU27 country.

This is why industry is calling for a workable transition period and agreement on continuing UK-EU cooperation in medicines regulation that recognises the sector as “different”. Whether it is different enough to sway EU27 negotiators who have bargained hard on issues such as the Brexit ‘divorce bill’ remains to be seen.

As we highlighted in our Guide to risk management and product launches, pharmaceuticals are a highly networked and globalised industry, integrated at multiple levels yet susceptible at all times to local variation. Market access in Europe involves a complex web of standardisation, harmonisation, communications, cross-border influences and intertwined supply routes, as well as countless departures from a nominally level playing field.

No country or healthcare system can manage medicines in a vacuum. Removing one significant piece of a jigsaw as intricate and interdependent as the EU, whatever compensatory arrangements may come into play, will reverberate across the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare provision for years to come.

(article continues below)

Trend #3: Do the drugs work for patients?

Patient-centricity is not just a way for the pharmaceutical industry to salvage its battered reputation. It is also a rational response to trends such as the digital revolution, personalised medicine, aggressive R&D investment in speciality and orphan drugs, patient empowerment, and the need to recalibrate overstretched healthcare systems towards disease prevention and healthy living.

It follows, then, that in a world where better-informed patients demand ever more say in therapeutic choice, and perhaps inevitably will end up paying more for it, there should be clear expectations about what claimed innovations can actually offer. This is especially critical in an emotionally charged area such as cancer.

Here, increasing disease prevalence, due in part to population ageing and the spread of unhealthy diets, lifestyles and environments in rapidly industrialising societies, has mobilised a stream of new targeted, premium-priced medicines, often promising optimal efficacy only in combination.

In the US, cancer drug costs rose from around US24 billion in 2011 to just under US$40 billion in 2015, while the number of oncology drugs in clinical development grew from 359 in 2005 to 586 in 2015. A more recent estimate from QuintilesIMS identified more than 630 distinct oncology-research programs in late-phase R&D, making up one quarter of the whole pipeline.

Costs aside, this should be good news for the swelling ranks of cancer patients worldwide. Yet a recent study by UK researchers in the BMJ found that, of the 68 cancer drug indications approved by the European Medicines Agency between 2009 and 2013, 57% (39) entered the market without evidence of a survival or quality-of-life benefit.

Among the 23 drugs that did improve survival, 11 failed to meet the European Society of Medical Oncology’s definition of a ‘clinically meaningful benefit’, the researchers noted. Many were approved on the basis of surrogate endpoints, despite evidence that these were often not reliable indicators of overall survival or quality of life.

Speaking for industry, EFPIA argued that the BMJ study focused predominantly on clinical trials, rather than real-world data showing actual patient outcomes. “The gathering together of overall survival data on new cancer medicines, generated in clinical settings, continues to represent a significant challenge both in terms of complexity and time,” it commented.

In cancer, the value of many treatments tends to increase over time, through impact on survival, or through use in earlier lines of therapy and stages of disease, EFPIA noted. For example, seven out of 10 cancer medicines approved by the EMA between 2003 and 2005 gained “additional approved value expansions” following their initial indication.

This again underlines the importance of pharmaceutical companies and healthcare systems allying to leverage extensive data resources that can demonstrate and monitor product value and outcomes in real-world settings (see Trend #1, above).

The iterative development model has long prevailed in cancer, although innovative ‘one-shot’ treatments, such as the recently approved CAR- T gene therapies Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel, Gilead) and Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel, Novartis), may come to challenge that paradigm, as well as opening up new discussions about how health systems can best absorb the costs of premium-priced medicines.

In the interests of medical ethics, economic efficiency and social solidarity, though, patients, payers, physicians and society have a right to know how limited healthcare funds are distributed and what exactly they are paying for.

Overall survival may be the gold standard of cancer endpoints; that does not mean every patient will prioritise duration of survival over benefits such as absence of pain or mobility. But patients should know as much as possible what is in store when they start on a new cancer therapy.

If industry is really invested in patient-centricity, it must embrace the kind of transparency that will align patients’ hopes and preferences more closely with the realities of drug development and therapeutic intervention in life-threatening diseases.

Trend #4: Digital medicine gets personal

The trend in recent years towards more accurate segmentation of disease types and personalisation of medicines has benefited enormously from scientific advances in areas such as genomics, cell biology and companion diagnostics.

However, there is another strand to personalisation. This is the growing role played by digital technology in ensuring that medicines do what they are supposed to do. One recent example was US approval of Otsuka’s and Proteus Health’s Abilify MyCite. This is an enhanced version of Otsuka’s antispsychotic Abilify, with an embedded ingestible sensor to aid therapy adherence by monitoring whether patients have taken the medication.

It was the first time the US Food and Drug Administration had approved a medicine with built-in digital tracking. The sensor developed by Proteus transmits messages to a wearable patch, which in turn sends dosing information to an app on the patient’s mobile phone. Patients can also authorise carers or physicians to access the same information through a web-based portal.

Other recent innovations that could drive personalisation of medicines reflect the emergence of fitness trackers, health monitors and other technologies geared to elucidating the ‘quantified self’. These conform both to society’s need for self-management and preventive healthcare that ease pressures on health resources, and with industry’s reliance on tracking outcomes in real time to substantiate its value offerings.

Examples include a new app for the Apple Watch Series 3, which promises more accurate measurements of heart rates and informs users when their heart beat rises above a preset threshold at rest.

Source: Apple

Meanwhile, wearables specialist Fitbit’s new Ionic smartwatch supplements the company’s existing activity trackers with more advanced health features such as a blood-oxygen sensor and an enhanced heart-rate monitor.

As well as offering pharmaceutical companies valuable time management tools, digital technology can aid personalisation of marketing strategies and messages, to address more accurately the needs of healthcare professionals or payers who have scarce time or appetite for face-to-face dialogue or traditional mass-market campaigns.

As product portfolios shift increasingly towards speciality and rare-disease therapies, customer communications must follow suit. Digital apps and networks are also a means of building productive and personal relationships with the end-customer, the patient, including wraparound support services that take a holistic view of disease management.

There is regulatory encouragement for these trends. In the US, for example, the FDA has introduced a pilot Digital Health Software Precertification (Pre-Cert) Program, to ease market access for health apps and other digital technologies in keeping with “the faster and iterative design, development, and validation used for software products”.

Pharmaceutical companies may need to do more, though, about stepping up to the digital plate. In PwC’s latest Global Digital IQ survey, only 63% of executive respondents in the healthcare and pharmaceutical or life sciences industry felt their CEOs were champions for digital, down from 72% in 2015.

Moreover, executives prioritised financial returns from their digital efforts. In 2016, 57% expected their digital-technology investments to boost revenues, compared with 46% in 2015. By contrast, only 3% of executives in 2016 expected digital investments to serve product innovation, down from 4% in the previous year’s survey.

Pharma might also bear in mind that digital technologies may eventually be competitors as well as allies. Virtual reality programmes to treat schizophrenia or chronic pain; non-invasive biolectronic wearables for psoriasis; or mobile medical applications offering cognitive behavioural therapy for substance-use disorders: these are all on their way or already on the market – and all of them are drug-free.

Trend #5: Will Amazon turn drug supply upside down?

Recent speculation about retail giant Amazon's intentions in the US have raised the spectre of a new, highly disruptive contender in the world's largest pharmaceutical market.

The speculation arose because Amazon was buying up wholesale pharmacy licences in a number of US states, as well as acquiring an organic-food chain, Whole Foods Market Inc. for $13.7 billion in June 2017. This move into ‘bricks-and-mortar’ outlets suggested Amazon was building a platform for distribution of prescription drugs across the US. Adding fuel to the fire were reports that the retailer was in active discussions with pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) on potential partnerships.

A 30-page report published by analysts at Goldman Sachs in August weighed up the options for Amazon in pharmaceuticals, including partnering with PBMs, establishing an online pharmacy, or setting up a retail network plus an online pharmacy, an integrated PBM, or a distribution channel to pharmacies.

The analysts high lighted Amazon’s evolved logistics network and ability to provide a superior user experience as factors that might give the retailer an edge in a drug-supply market worth $125 billion each year, or 30% of net US pharmaceutical spending.

As usual in pharmaceuticals, nothing is quite that simple, not least the complexities of state pharmacy regulations and the particular skillset needed to compete as a PBM. For the time being, Amazon appears to have shelved any drug-specific plans in favour of supplying medical devices and equipment from its warehouses. However, some analysts believe the retailer will be ready to go in the pharmacy market by 2020.

The extent to which Amazon has redefined shopping habits in the general retail market gives some indication of the impact it might have on the existing drug-supply network, particularly in terms of driving efficiencies and stripping out extraneous costs.

In the US market, this comes at a time when PBMs are under scrutiny over their influence on the end-prices of medicines. The pharmaceutical industry accuses PBMs of pushing up prices by demanding ever-larger rebates, without passing on many of these savings to insurers or patients. For their part, PBMs contend that only drug companies can set list prices, so must take the blame for cost inflation.

While this debate might suggest industry would welcome the entry of a disruptive player such as Amazon into the drug-supply chain, it should also be careful what it wishes for. Some analysts foresee negative effects on pharmaceutical sales overall, with Goldman Sachs predicting that Amazon would push for more price transparency and lower out-of-pocket costs for patients.

Given the veil of secrecy that still hangs over the pricing of medicines, this might be a Pandora’s Box the industry would prefer to keep the lid on.

Trend #6: A long way to go with Alzheimer’s

Our last trend for 2018 relates to the very heartbeat of the industry, its research and development process.

For all the undeniably impressive progress made in improving the management of cancer, diabetes, heart disease, asthma, rare diseases or mental-health conditions, some major and demographically driven health issues remain impervious to therapeutic intervention beyond the merely symptomatic.

A case in point is Alzheimer’s disease, where the recent failure of Axovant’s intepirdine in late-stage development was just the latest in a long run of disappointments. A Medicines in Development update from US industry association PhRMA identifies 87 potential new treatments currently in clinical trials for Alzheimer’s. Between 1998 and 2014, though, 123 medicines for Alzheimer’s dropped out of clinical development, while just four were approved – none of them addressing the underlying causes of the disease or slowing the rate of decline.

As PhRMA points out, in the US alone deaths from Alzheimer’s have increased by 89% since 2000. Mortality from heart disease fell by 14% over the same period. It is estimated that Alzheimer’s and other dementias will cost the US health care system more than $259 billion in 2017, potentially rising to $1.1 trillion by 2050.

At one level, these challenges validate the significant role the pharmaceutical industry still has to play in understanding, managing or preventing diseases that will have enormous and far-reaching effects on all of our lives in the future.

But if industry wants to reverse the negative perceptions that make it an easy target for market access restrictions, and prove its worth as a linchpin of sustainable health systems, it must show wholesale commitment to tackling those diseases with the most chilling implications for long-term healthcare provision, economic stability and social cohesion.

As with many of the key challenges facing the industry, the most promising solutions are likely to come from global co-ordination, new forms of public-private partnership, and tapping into the wider health and scientific ecosystem.

As Pierre Meulien, Executive Director of Europe’s Innovative Medicines Initiative, comments: “Collective solutions, working in a non-competitive (or pre-competitive) space, will be mandatory to address the biggest health challenges, like Alzheimer’s disease and antimicrobial resistance.”

The post-human-genome world, Meulien adds, is one where “a multi-disciplinary, multi-sectoral approach to problem solving will be essential and where models of open innovation will thrive”.

TRiBECA® Knowledge is a market leader in smart business tools that help pharmaceutical companies successfully launch and commercialise products. Our tools enhance visibility and transparency, streamline processes and drive communication and collaboration across brands, management layers, business functions and countries worldwide.

Andre Moa

Andre Moa

4 Jan 2018

4 Jan 2018

20 minute read

20 minute read